In 2013, I ran a series of workshops for designers with Scott Sullivan exploring the connection between physicality and emotions. This article is a reflection on some of those ideas and how they apply to product design. Are you ready to get a little weird?

Introduction

As the IoT takes off, the physicality of digital design becomes more and more important. This article explores some of the ideas around the connection between physicality and its emotional impact though a discussion of Laban Movement framework.

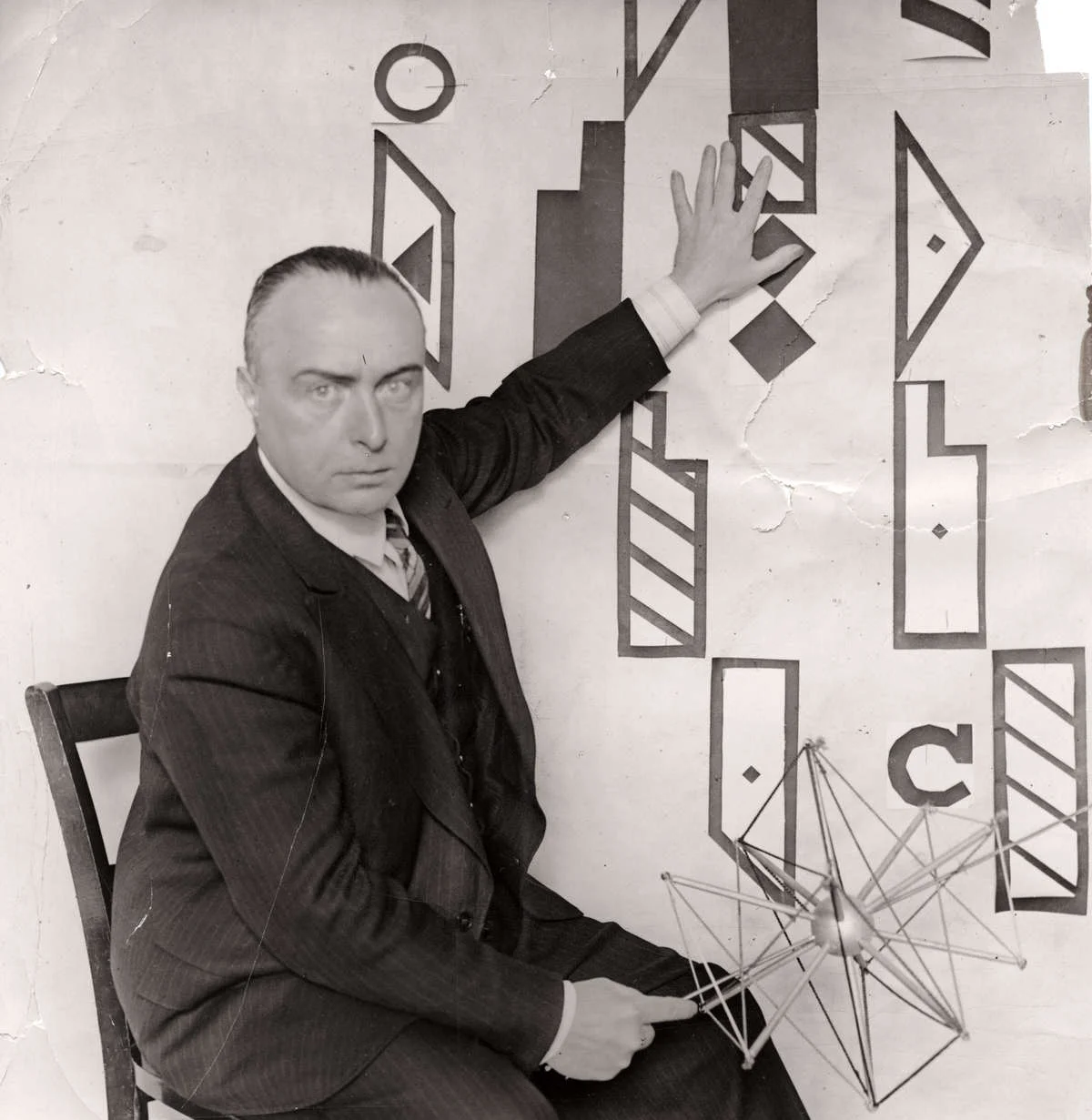

Rudolf von Laban aka Rudolf Laban (1879-1958) developed theories and frameworks of human movement that were applied to dance, acting, visual arts, education, and even efficiency studies of factory workers. He is most notably known for pioneering European modern dance and Laban Movement Analysis and his Labanotation, a complicated dance/movement notation. His philosophy and theories were based on the belief that the human body and mind are inseparable. Our physicality is unmistakably fused to our mental states and vice versa. It is this connection between posture and emotion that we’ll explore in this article.

While Laban is best know for his work and contributions to modern dance, his framework can be abstracted out and applied to the physicality or posture of product design, and even to simply lesson about human movement that can influence how we interact with each other in mundane ways.

Example One: Fitbit One

Let’s explore this connection with an example. Several years ago I bought a Fitbit One to track my steps and sleeping. I was particularly interested in the sleep tracking feature, because I have sleep apnea and use a CPAP machine while I sleep.

Let me set the stage for you. I typically went to bed after my wife, so I would often walk into a pitch black bedroom not wanting to turn on lights and wake my sleeping wife. I would undress and put the fitbit One into the wristband and put it into SLEEP mode all in darkness before lying down to sleep. If you aren't familiar with the fitbit One, to put it into sleep mode you need to hold down the button on the face of the device until it switches modes. I would do this every night, and every night I had the same jarring experience. This is what I would see:

In the middle of the blackness of my bedroom, this bright light would flash to life and start counting down my hopefully multi-hour sleeping session in tenths of a second...tenths of a second. Ouch, I winced every time it happened. I knew this interaction was broken, but didn’t quite have the right language to fully explain why it was broken until we started exploring Laban Movement Analysis for our workshop on movement and emotions.

Laban cataloged human movement into 3 factors (sometimes called spectrums or dynamics) of Weight, Space and Time. These efforts have opposing poles or elements: Weight (Strong - Light), Space (Direct - Indirect), Time (Sudden - Sustained). Each of these individual factor elements are combined to create 8 fundamental efforts of movement.

So if we map my experience of this interaction with the fitbit One we get something like this

There was a strong, bright light in the middle of a darkened room. It was directly interacting with me in front of my face, and it was very rapidly counting down the time in tenths of a second.

So, according to Laban when we combine these three elements of Strong (weight), Direct (space), and Sudden (time) we get the effort Laban calls “punching!” So, the fitbit One was essentially punching me in the face 10 times a second as I’m trying to go to sleep. I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to be punched to sleep every night.

So, the Laban framework gives us a new language to better describe the materiality of these types of embodied interactions we have with technology products. The framework also gives us levers we can use to adapt or change these interaction. If we flip each of these factors of putting the fitbit One into sleep mode we get Light, Indirect, and Sustained, which is what Laban calls “Floating.” Now floating is much closer to the ideal embodiment I want to interact with as I’m trying to go to sleep. Wouldn’t you rather float to sleep than be punched to sleep?

Let's Try It For Yourself

Try it while you are sitting there reading this. I don't mean try falling asleep, but try moving your arms in both of these ways: punching and floating. You can do it while you are sitting there. Seriously, just try it.

First move your arms in a strong, direct, and sudden manner. It should reflect a kind of punching motion, but it may not look exactly like a traditional punch. Just do it. There's no wrong way to do it. I'm not watching, but I'll be here waiting for you. You really need to experience it to get the full impact. Did you do it? How did that feel?

Now move your arms in a light, indirect and sustained way. It may appear that your arms are floating through space. How did this effort make you feel? Did you feel different when you were punching versus floating? I suspect you did.

Was there anyone around you while you were trying this? If so, ask them how they felt when you moved in each of these ways. Or better yet, ask them to try it for themselves. These embodied interactions have both an impact on the actor exhibiting the effort as well as all the actors interacting or exposed to the effort.

I think we can all agree that floating to sleep sounds and feels much better than being punched to sleep.

Unfortunately, fitbit got the embodiment of this interaction completely wrong, at least according to the Laban framework.

Example Two: Fitbit Flex

Let’s look at another example from fitbit, the fitbit flex. After using the fitbit One for a while, I picked up a fitbit flex shortly after they came out to give it a try. Did they correct the embodiment issues from the fitbit One? Let's take a quick look and see what happened.

Here is what it looks like to put the fitbit flex into sleep mode. There’s not “button” because the device is hidden inside the bracelet sleeve. So, to switch modes you need to rapidly tap the device until it switches modes.

Different? Yes. Better? Hmm. I'm not sure.

So they’ve turned the tables with the flex. According to Laban framework, it’s still punching, but this time I’m punching the fitbit flex instead of it punching me. Payback is a bitch, right?! Well, it’s still broken and I still don’t want to continue a nightly ritual of punching my devices before I go to sleep. It’s just not right.

…and did you catch what happens when the flex flips into sleep mode? Did you see it? Yep, a creepy little set of eyes watching me. Not only am I punching my device, but it confirms that I’ve punched it enough by telling me that it will be creepily watching me all night long.

Final Thoughts

This is all a little unsettling. The embodiment choices we make for the products we are designing matter and they impact the people’s emotional state when interacting with these products.

Frameworks like Laban Movement Analysis can start to give us a language and levers to make products with better embodied interactions. It should probably be noted that we (and the products we make) rarely exhibit one and only one of these efforts, we are typically a dynamic combination of these efforts, which I'll discuss more in the next article. In the meantime, you can try exploring each of these efforts on your own, either with your whole body or with your arms again sitting in your chair or walking down the street.

What is the identity of the product you are making? What type of relationship or interaction do you desire it to have with people? How do you want people to feel before, during and after they use the product or service you are working on?

While I've picked on fitbit examples in this article, this isn't a problem exclusive to fitbit, but these examples were personal and ready at hand. Let's look at one more non-fitbit example. You are probably familiar with automatic soap dispensers in some public bathrooms. You place your hand under the device and it automatically dispenses soap. You probably haven't given much thought to the way the soap is dispensed right, but someone made design choices and the soap has a physical embodiment that interacts with you.

A couple years ago, there was a soap dispenser I would regularly use in the office building where I worked. It would lazily dispense soap in a slow, relaxed manner. It is probably going too far to say it was relaxing, but it was calm and unobtrusive. According to Laban, it would have been "gliding" or light, direct, and sustained. But to be honest I never gave it much thought. It played a supporting role in the environment, it was part of the behavioral infrastructure and the embodied interaction wasn't broken or jarring...until one day everything changed.

I guess the soap dispenser's previously calm nature was attributed to a slowing dying battery, because one day the same dispenser's character completely changed, to what I can only attribute a battery change. It now dispensed soap in a very authoritative and commanding manner. It was now strong, direct, and sudden or punching/thrusting again. My calm soap companion was now punching me clean several times a day. We soon became adversaries and I dreaded our daily confrontations.

All these little choices matter and the interactions we have with all these products accumulate throughout the day. As we move through the built environment, are the products and services you are making adding to the stress in people's lives? How are the things we are making emotionally impacting people using them?

Take some time today as you move through the world to define or reflect on the embodiment of the objects you interact with and let me know what you find.

This article is also published on Medium if that is more your speed.

In the next article, I’ll discuss some of the results from the Laban workshops, and the implications on physicality, emotions and relationships.

If you are developing a product or service and need help with the physical embodiment and interactions or just want to learn more about how frameworks like Laban Movement Analysis could help with your product design, let's talk.